At a lecture at the London School of Economics in 2017, Jeffrey Sachs called for the economics discipline to provide better answers to urgent challenges relating to human flourishing and environmental sustainability. Yet in order to do so, he argued, it will be necessary to start with a new and improved ‘economic anthropology’1. That is, we need a new picture of the human being as the starting point for the basic assumptions – and objectives – that frame our economic thinking.

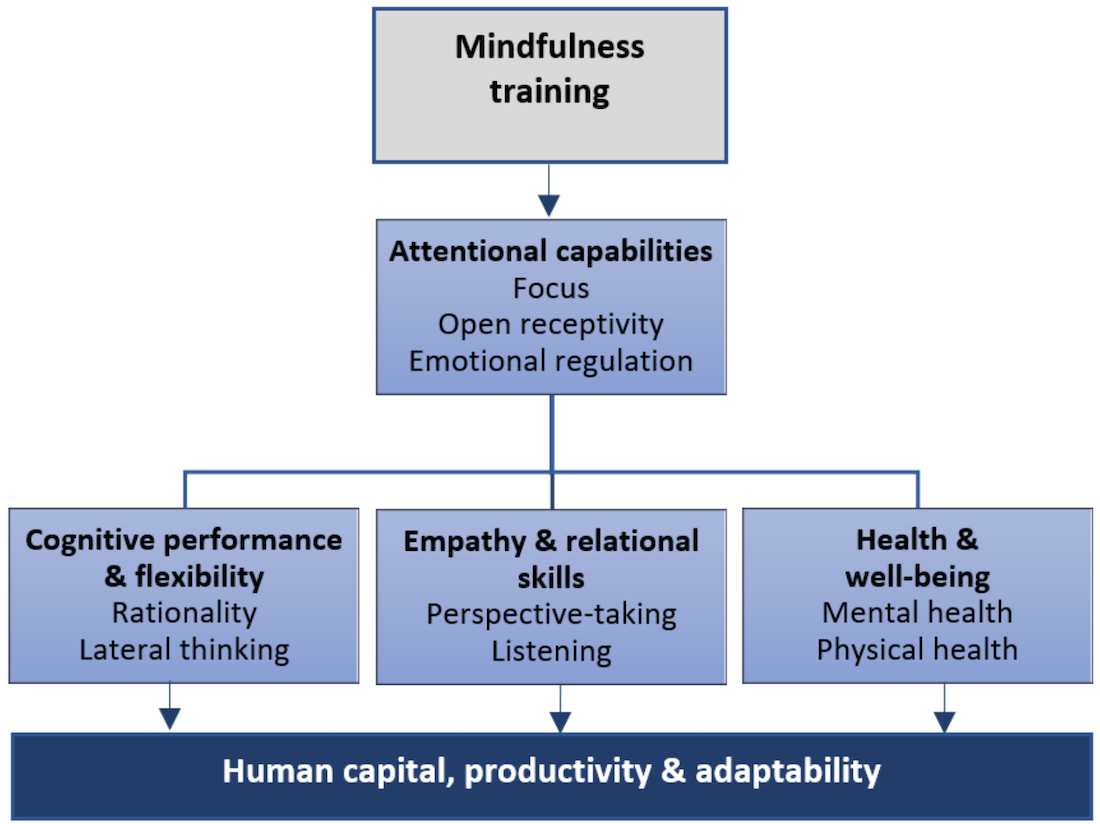

Similarly, in this series of articles we begin with the idea that the cultivation of our inherently human capacities should be placed at the center of a long-run plan for sustainable prosperity. Specifically, we explore whether cultivating mindfulness – paying attention to one’s present-moment experience with an attitude of openness, curiosity and care – could help us to foster precisely those capacities needed to support an economy that is more productive and more adaptable, yet at the same time more sustainable, over the coming decades.

What Is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is basically awareness. It means the ability or tendency to pay attention to what’s happening in the present moment in the mind, body and external environment, with an attitude of openness, curiosity and care3. It is best thought of as an inherent human capacity: we are all somewhat mindful, some of the time. We can, however, cultivate this capacity. This is done through mindfulness practice. For instance, simple meditation exercises help individuals to practice focusing their attention (e.g., g on the sensation of breathing) as well as practicing a wider, open monitoring of their present-moment experience (eg scanning the body to notice the various sensations that might be present).

These practices are often bundled into mindfulness training programs, which are designed to help people develop an awareness of thoughts, emotions, and physiological reactions, delivered via teacher instruction, practice and group discussion. Over the past few decades, such training programs have become popular in a range of settings including in healthcare, schools, and workplaces4 .

Such a paradigm shift would be especially fitting in response to two trends which look set to radically reshape societies in the 2020s and 2030s: the prospects for environmental sustainability, first of all, and the impending wave of technological changes that will transform economies via advances in artificial intelligence, Big Data, the Internet of Things and more.

What would a more ‘mindful’ economy look like? For what follows, we consider a scenario in which there is a sustained uplift in the average ‘level’ of mindfulness across the population as a whole, which is assumed to take place gradually over the coming years. While detailing how we would achieve such an uplift in mindfulness lies beyond the scope of this series of articles, it would require public and and private investment in mindfulness training program across schools, workplaces and other access points for the adult population. Such a plan in effect treats access to mindfulness training as a kind of basic public amenity – something we need for the future economy to thrive with a workforce that can be calm of mind and body.

Our intention here is to stimulate discussion around the potential role that mindfulness could play in shaping macroeconomic objectives and outcomes. This series of articles is the first contribution to explore this topic systematically. The approach taken is to draw together various strands of scientific research linking mindfulness training to aspects of human functioning relevant for macroeconomic outcomes.

We do not make projections using formal economic models here. We also set aside, given our focus on the ‘macro’ picture, other ways in which mindfulness might affect our economic lives, such as our experience of work or the nature of our economic relationships2 . That said, in related articles we will provide a critique of the standard homo economics assumptions of economic theory, and put forward an alternative picture of the human being: one which takes our environmental context as primary and which is grounded in human capacities of heart and mind, such as awareness and empathy.

While its potential could be very significant, mindfulness is not a panacea. To begin with, scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of mindfulness training, while rapidly expanding, is still at a relatively early stage in many areas of human functioning. More generally, other approaches are also clearly needed to form a broader economic strategy.

The cultivation of mindfulness could fit particularly well alongside other approaches which are aimed towards broader metrics of well-being than GDP per capita, especially those geared towards reducing poverty and inequality and promoting a greener economy.

About the Author

This excerpt was edited and reprinted with the permission of our friends at The Mindfulness Initiative. To learn more about their work, please visit www.themindfulnessinitiative.org. View the original work.

View References

1 See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajrJbnXTwL8&feature=youtu.be.

2 Moreover, the suggestion is not that mindfulness only has ‘value’ instrumentally. See, for instance, Nixon (2018).

3 See https://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org.uk/.

4 For an overview, see Crane et al (2017) and The Mindfulness Initiative (2015)